The Performance Failure Point and the Ego

By Borderland Nathan

If I were to point to a single concept that is absolutely critical for continued growth in pretty much any area of life, it would be this: Test yourself to failure. The reason why is that this is fundamental to human knowledge itself; it was pointed out as far back as Aristotle that to truly understand a concept, you must know both sides of the coin, so to speak. I can hold a penny in my hand, and only see the tails, but the only reason I even know which side is tails or what “tails” even is, is because I know the other side has heads.

In systems science terminology, you must know both sides of a system boundary to know that it is in fact a boundary, and then you can truly profess to understand the component that you are studying. There is a top-down as well as a bottom-up quality to knowledge, and this extends naturally into physical training.

To use a more personal example, when training on the mat in boxing or Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, the results of progress are real, and it is right to take pride in your accomplishments. Every successful technique and round is confirmation that you are on the right path, and your training model is applicable to an ever expanding set of variables. You tell yourself, and it seems to be true, that you are completely comfortable with failure because then you know how to correct course and become even better. At a certain point though, people seem to be catching up in skill. Certain guys that you were able to hang with on the mat are getting the best of you, and you end up more tired at the end of class than you used to be.

This is the critical point of your journey.

At this crossroads, you have already unknowingly gone down the wrong path, but you are still at a fork in the decision tree of progress. You have a couple choices, the first being the easy path, in which we set our own performance boundary subjectively rather than allowing reality to show us the ugly truth. After all, we don’t need a new set of goal posts if we insist that the opponent play by the ones we refuse to leave. The second path is to ruthlessly address what has clearly shown itself to possibly be the near side of your performance limits. But is it really? Only an appropriate strategy to be outlined shortly will tell for certain. So let’s take a look at each of these two choices more closely.

The Easy Path

I was quite proud of my ability as a smaller practitioner to deal with larger, stronger, and even higher belt level grapplers. It took a high level of technique to offset the weight advantage and sheer power level, and I was rightfully quite proud of my technical skill. The problem at this level is that expectations can kill if not viewed properly. My coach expected me to do well, I expected myself to do well, and sometimes even the other guy expected me to do well. If I did not do well, one of my sneak little cognitive biases in action was to play the “technical game.”

1. “The technical excuse”

He wouldn’t have overwhelmed me if he hadn’t been using brute force. I refuse to stoop to his level and forsake technique, and he “should” have deferred to that agreed upon understanding. After all, isn’t that we are here for? This can lead to a fair bit of anger with training partners, as I came to see a few among them as playing foul to win. I was doing real Jiu Jitsu, they were doing something else to “win.” That must mean they were here for the wrong reasons.

2. Choosing partners

Sometimes this is a perfectly acceptable approach, because certain people simply are too much for you to handle, and may not have the control necessary for you to safely roll with. Perhaps you are injured, or there is some other circumstance that makes it unwise to have that person as a partner during a match, and your coach will often take this into account when pairing you up. But the key here is that this choice arises from the understanding of your own limits as well as the opponent’s capabilities. In my case, I used excuse A as a justification for avoiding the tougher opponents that I knew would overwhelm me. I wasn’t worried about getting hurt, deep down I was afraid of failure. More importantly, I was afraid of really knowing and accepting that failure. This was especially acute when I knew the battle would be from an equal or lower ranked belt.

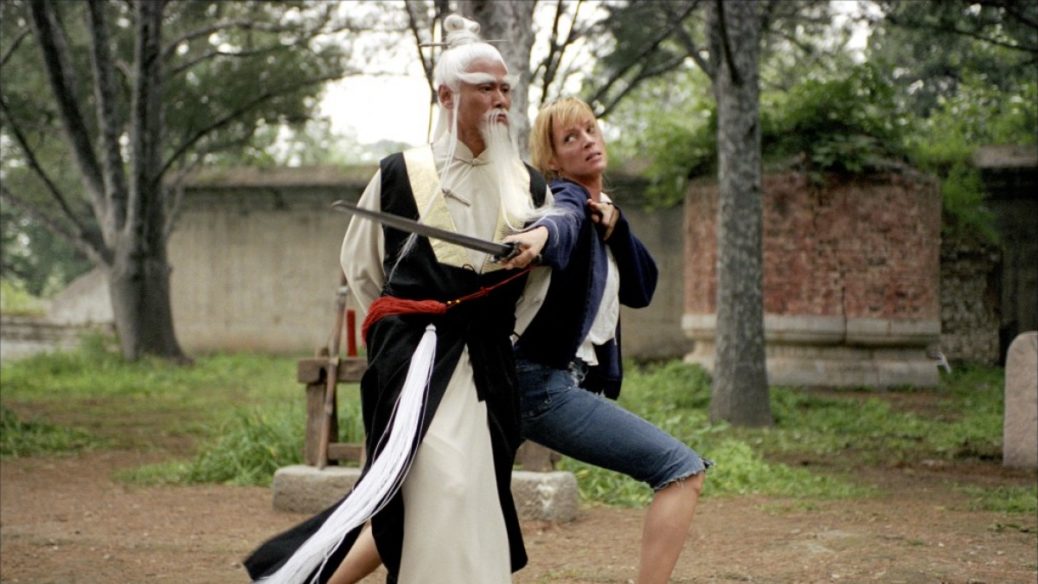

3. The Zen Master routine

This final strategy is perhaps the most obnoxious, and it happens when you are truly headed down the dark path. We’ve all seen it, and at one point I was just as guilty. When I couldn’t avoid the opponents that I knew would be a battle, I would “play” with them. I would use extremely slow, technical movements that never really committed, so then they could never really fail. He obviously passed my guard because I wasn’t really trying, because after all I am a good sport, a true practitioner of the gentle art, and I would never use the raw power of my belt ranking to overwhelm his aggression.

The real key is to practice slow, loud, deep breathing while doing this. I would keep my eyes open but staring off at a point somewhere beyond the opponent, so he could see that I was so unconcerned by the lack of effort that I was contemplating life’s greater mysteries. The best was when after the match he would ask tentatively “Did I really get that submission I caught you in?” “Of course” I would answer, with just enough tone to insinuate that I was trying to boost his ego at the expense of his failure.

That’s when I realized I was an asshole.

The Hard Path

The irony was that yes, he really did get the submission, because at that moment he was better than me. And he is my partner, not my enemy. He deserves to know his capabilities, as do I, because in real violence is not the time to find out the other side of the coin by a trip to the afterlife. I was the one that was not practicing Jiu Jitsu, and my actions and outlook may have seemed subtle but were in fact incredibly arrogant.

My professor was the one that had noticed this before I did, and this is why it is so critical to continually surround yourself by not just your peers, but your betters. First, he began giving me over to the people I hated, the ones with attitude problems that were cocky and had the game to back it up. They may even be lower belts, to add insult to injury. Then, he would point blank tell the other guy “Use your size,” before turning to me and saying “Use your speed.”

That’s when my eyes were opened. Who am I to determine what Jiu Jitsu is for him? He has his own body, his own hopes and fears, his own challenges and demons to fight on the mat. And yes I mean that in all seriousness, the mat is where men are made, and that “mat” can be found in many places in life, from the peer review process to the boxing ring. Some larger opponents in Jiu Jitsu can’t hope to be as fast as I am, so why do they get to deny their own power and attributes for my sake? Is Jiu Jitsu mine? No, only my Jiu Jitsu is mine.

I talked to my professor several times candidly about this flaw I noticed, and as always he was equally tactless in his broken English in explaining why I was starting to suck. It hurt. And it was true. I was good, but good didn’t matter when he and I knew I could be great. The problem wasn’t my skill level, it was my performance model. Both a good and a bad performance model can lead to a real skill level, but your real skill level isn’t necessarily your true skill level. I already knew what I could do, now I needed to know what I couldn’t, so that I could really know what I could do. I saw the near side of the coin, I needed to see the far side to know that the near side was tails. So I took steps to do exactly that.

1. I instantly chose whichever partner made me least comfortable

I made it a habit. He’s big? Give me that guy. I suck at closed guard and he likes to pass it? Give me that guy. I am exhausted and that guy is built like a human refrigerator? Give me that guy. I didn’t think, because I would rationalize. It needed to be by default to pick the least desirable option. It was time to expose myself.

2. I focused on technical perfection

By technical perfection I mean full, complete techniques, that may or may not fail. No half assed “flow rolling” during a match that was not a flow roll. I needed to know where I was getting things wrong, and I could only do that by performing everything as perfectly as I knew how, with full effort, and mentally marking the exact point of failure. This let me approach my own “game tree” and work the kinks out near the trunk that would affect the branches later.

3. I would congratulate him sincerely after the match

I was told by a friend in a more thoughtful moment, that “the other guy deserves to have his day too.” I want him to after all, because if he doesn’t become skilled, I don’t become more skilled in the future. I am the sum of experiences with my training partners. I thanked my partner for a variety of reasons: humbling me, doing an excellent job, showing me my game, and showing me the way to move forward.

4. I would have him show me after the match, not during, what he did to win

The first step was where I found out that my game was weak, this is the step where I found out how my game was weak. A man that has bested you and been congratulated by you is only too happy to show you how he did it. I kept the issue small, there was no point in telling myself that I sucked, I needed to pick the exact moment that I had a system failure and begin problem solving. I would often ask the coach to come in, but only after I had finished a workable solution myself. The importance of asking after the match was to avoid the trap of eating up hard rolling time to run out the clock with drilling, when the goal was testing ourselves on the mat.

This final step rounds out what ends up being an entire process of growth with your partner. You tried, you succeeded or failed, you found out your true boundaries, and then you made not just real but true progress, all with the same person. By following this process myself, I came to really love Jiu Jitsu instead of fearing it.

That is what performance is all about.

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar