There Is No Trust without Love: Reflections on Quinquagesima

by Borderland Nathan

Let’s start this with a bang and let Saint Paul set the tone.

1 Corinthians 13:1-13:1)All citations are taken from the RSVCE.

If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. 2 And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. 3 If I give away all I have, and if I deliver my body to be burned, but have not love, I gain nothing.4 Love is patient and kind; love is not jealous or boastful; 5 it is not arrogant or rude. Love does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; 6 it does not rejoice at wrong, but rejoices in the right. 7 Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.8 Love never ends; as for prophecies, they will pass away; as for tongues, they will cease; as for knowledge, it will pass away. 9 For our knowledge is imperfect and our prophecy is imperfect; 10 but when the perfect comes, the imperfect will pass away. 11 When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child; when I became a man, I gave up childish ways. 12 For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood. 13 So faith, hope, love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love.

There are two themes I am going to highlight here, the first is that of love, and the second which I will cover later is the idea of seeing dimly as a child versus seeing clearly as an adult.

Love

When Saint Paul talks about love, he isn’t talking about just any love. He is speaking of supernatural love, or what we call charity. Charity is from the Latin word caritas. I didn’t really understand the difference when I was younger; I really just thought of it as love + holy feelings of some sort. You can give a homeless guy some McDonald’s, get a warm and fuzzy feeling and that’s “charity.” But Saint Thomas talks about this, and put it in a way that made sense for me. All people naturally desire something that they perceive as good. Even if you wanted to do something awful, it’s because doing something awful is in some way considered better than the alternative. It’s simply wired into how people are: we are creatures designed to pursue ends, and those ends have to have something that makes us pursue them. This concept is called good.

I have an atheist buddy that is constantly talking shit about the Ned Flanders-type do-gooders of the world, and he makes exactly that point. He likes saying that the only reason Catholics do things for people, hell the only reason anybody does altruistic deeds for anyone, is ultimately selfish: You are pursuing the nice feeling you get for helping people, or you are pursuing the intellectual gratification you get for “being good.” He doesn’t say that’s wrong, his point was that all altruism was selfish at its core. We never really do anything for purely selfless reasons.

And here’s the rub: Saint Thomas would probably agree. Pursuing ends that we perceive as good in some way is baked into being human, and so in some sense we never escape our own paradigm. We are always at the very least treating our own assessment of the situation as to be acted upon, and therefore good. It’s impossible not to, because we are subjective creatures.

The idea of charity, is that is impossible to have as a human; it is only achievable by grace. We call it a theological virtue, and charity is the type of love that loves God, and therefore loves the other person according to the objective standard of God: for their own sake. 2)See Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II of II, Q. 24, Art. 2, and De Caritas, Art. 4. If the normal concept of love is willing the due good of another, or at least from within your own paradigm and understanding of what that person and due good is, charity is perfectly willing the due good of the other in himself, apart from your imperfect paradigm. God does things with this type of love. He changes the world with this type of love. This type of love rarely makes sense but it cracks hearts and makes men cry at the stars when nobody is there except themselves and the whispers of their thoughts.

Charity simply is grace. It is God’s presence poured into us, and without it, anything we say or do takes on a lesser, cruder, uglier meaning. With charity we are sons of God and perform the acts of sons; without grace we are rational animals, with all the flaws and failures that entails. Let’s turn to the Old Testament reading for today from the Roman Breviary.

Genesis 12:1-19

Now the Lord said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. 2 And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. 3 I will bless those who bless you, and him who curses you I will curse; and by you all the families of the earth shall bless themselves.” 4 So Abram went, as the Lord had told him; and Lot went with him. Abram was seventy-five years old when he departed from Haran. 5 And Abram took Sar′ai his wife, and Lot his brother’s son, and all their possessions which they had gathered, and the persons that they had gotten in Haran; and they set forth to go to the land of Canaan. When they had come to the land of Canaan, 6 Abram passed through the land to the place at Shechem, to the oak[c] of Moreh. At that time the Canaanites were in the land. 7 Then the Lord appeared to Abram, and said, “To your descendants I will give this land.” So he built there an altar to the Lord, who had appeared to him. 8 Thence he removed to the mountain on the east of Bethel, and pitched his tent, with Bethel on the west and Ai on the east; and there he built an altar to the Lord and called on the name of the Lord. 9 And Abram journeyed on, still going toward the Negeb.

10 Now there was a famine in the land. So Abram went down to Egypt to sojourn there, for the famine was severe in the land. 11 When he was about to enter Egypt, he said to Sar′ai his wife, “I know that you are a woman beautiful to behold; 12 and when the Egyptians see you, they will say, ‘This is his wife’; then they will kill me, but they will let you live. 13 Say you are my sister, that it may go well with me because of you, and that my life may be spared on your account.” 14 When Abram entered Egypt the Egyptians saw that the woman was very beautiful. 15 And when the princes of Pharaoh saw her, they praised her to Pharaoh. And the woman was taken into Pharaoh’s house. 16 And for her sake he dealt well with Abram; and he had sheep, oxen, he-asses, menservants, maidservants, she-asses, and camels. 17 But the Lord afflicted Pharaoh and his house with great plagues because of Sar′ai, Abram’s wife. 18 So Pharaoh called Abram, and said, “What is this you have done to me? Why did you not tell me that she was your wife? 19 Why did you say, ‘She is my sister,’ so that I took her for my wife? Now then, here is your wife, take her, and be gone.” 20 And Pharaoh gave men orders concerning him; and they set him on the way, with his wife and all that he had.

The first question I ask is, why are we mentioning Abram? During these pre-Lenten days, the Old Testament reading for today from the liturgy of the hours covers a series of patriarchs, from Adam onward, and shows how they point toward Jesus as their fulfillment. The patriarchs are imperfect symbols of Israel, and all of them in turn point toward their perfect fulfillment in Christ.

Abram, a polytheist pagan, is approached by the living God and told to pack up all his things and leave for a distant land, far away from everything he has ever known. In return, he receives a 3-part promise: God will make of Abram a great nation, he will make his name great, and in him all the families of the earth shall be blessed. 3)Scott Hahn, Kinship by Covenant: A Canonical Approach to the Fulfillment of God’s Saving Promises (Newhaven: Yale University Press, 2009), 103. That’s it. And off he goes into the desert.

The early fathers liken this to the Purgative Way, as he relies on trust and releases his grip on everything he has. The meager possessions it speaks of him gathering later in the passage are bare necessities, because to the Semitic mind he is losing everything that is important by losing his family, his father’s house and therefore earthly inheritance, and the land in which he lives. This also means he is losing his culture, since culture is based on cult, and therefore worship. God is demanding that he give up other gods and worship only him. He is demanding absolute loyalty, fidelity, and worship, and Abraham steps into the void.

The desert is a period of trial, and Abraham is prefiguring in his journey the future travails of Israel and Moses in the desert. He treks the basic path to be followed later by Israel, and ourselves as the people of God, both physically and spiritually.

Scripture often uses literal physical geography to map our spiritual concepts, and this is followed within Catholic tradition as well as literature such as in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Moving toward holiness is tied with going up, usually a mountain, where the believer communes with God. The garden of Eden was on a mountain, covenants are formed on mountains, Jerusalem itself would be built on a mountain. Going “up” to God was taken literally and spiritually, and contrariwise going “down” also had a negative association with sin and vice. Death and sin were in valleys, and associated with “going down.” This was meant literally and spiritually in the phrase “going down to Egypt,” because Egypt was seen as a cesspool of sins of the flesh. “Going down into Egypt” was synonymous with failing to trust in God, precisely because of these events.

Abram is shown as moving up mountains and building altars there to praise the Lord, and he continues on to Negeb, a desert region, where he faces his first trial: a famine. At that point he has a decision to make: he can trust in God, or he can descend into Egypt and receive help from the rulers of the world. Likewise, we can “ascend the hill” to Jerusalem to our altar in the form of the Mass, and then we leave Mass and live our lives as Abram did in the desert of Negeb, until we face our first trial as we fight through the Purgative Way. These trials test our ability to let go of our tight grip on control of earthly things and circumstances in our preoccupation with avoiding suffering and death. They test our ability to trust in God.

Abram presumably had a good reason, the passage notes that the drought was severe. Canaan had irregular rainfall and drought was common, and the Nile was a more stable food source. It was the standard response for people to go to Egypt in this situation. 4)Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1–15, Word Biblical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1987), 287. And yet the point of the text is not to say that Abram was justified, it was to set up the test: That even though the reasoning was sound, the drought was severe, and everybody goes to Egypt for food, this was not the place of God’s promise.

It said Abram went to sojourn there, and only to stay temporarily. Likewise we can tell ourselves that we are only doing something wrong because of our extreme circumstances, and that we will make things right with God as soon as the emergency has lifted. I remember that when funds were tight, tithing was the first thing I would skimp on. When my dad got dementia and I needed a lot of money fast, I worked as a bouncer in a strip club. I chose Egypt. I told myself I would just do it for awhile, until I got his situation taken care of. I hustled, made about sixty an hour tax free, and was able to handle my earthly concerns. I also faced regular extreme violence, worsened my PTSD, and ended up in court, among other things. God is life. Egypt is death. When we choose the other path, unintended consequences often follow and things begin to slowly unravel.

The very fact that Abram was in Egypt had its own unintended for Abram as well, as he found himself having a problem: He had a smoking hot 65 year old wife and the Egyptians were a bunch of ravenous slutty man tarts. He was concerned that Egyptians respected the sanctity of marriage so much that if they found out he was married to her, they’d have to murder him to avoid committing adultery. 5)See Didymus the Blind’s and Saint Ambrose’s commentary on the passage in Mark Sheridan, ed., Genesis 12–50, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture, Old Testament II (Downers Grove: Institute of Classical Christian Studies, 2002), 7-8.

Salma Hayek is 58. Just saying.

So what does our stalwart spiritual leader do? He whines like a bitch to his wife and has her pretend to be his sister. The rationale was that this would lower the danger from being a husband to rather being a brother, in which case at worse he would have to send away a litany of suitors trying to marry Sara’ai. 6)Umberto Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Genesis, Part II: From Noah to Abraham (Jerusalem: Varda Books, 1992), 350.

Saint Didymus the Blind, a saint from Alexandria, Egypt, explained that it was the custom in Egypt and even in Abram’s own lands to marry a sister or near blood relative referred to as such. Saint Augustine, a hardliner against any form of lying, explains how this isn’t a lie.

Saint Augustine:

Having built an altar there and called upon God, Abraham proceeded thence and dwelt in the desert and was compelled by pressure of famine to go on into Egypt. There he called his wife his sister, and he told no lie. For she was this also, because she was near of blood; just as Lot, on account of the same nearness, being his brother’s son, is called his brother. Now he did not deny that she was his wife but held his peace about it, committing to God the defense of his wife’s chastity and providing as a man against human wiles. 7)City of God 16.19.

It wasn’t a lie, but neither was it an ideal situation. In fact I see echoes in this patriarch of Adam’s sin in the Garden, where he failed to keep his wife safe from the serpent. This inversion of roles and failure to sacrifice on behalf of his spouse is strikingly repeated in Abram’s Coen Brothers’ style hijinks.

I’ve seen many modern protestant commentators and commentaries try to say that Pharaoh defiled Sarai’ai’s virtue. Well, two doctors of the Church, both East and West, say nothing happened. 8)See Saint Augustine, “And far be it from us to believe that she was defiled by lying with another. It is much more credible that, by these great afflictions, Pharaoh was not permitted to do this,” Ibid., and Saint John Chrysostom, “What imagination could adequately conceive amazement at these events? What tongue could manage to express this amazement? A woman dazzling in her beauty is closeted with an Egyptian partner, who is king and tyrant, of such frenzy and incontinent disposition, and yet she leaves his presence untouched, with her peerless chastity intact. Such, you see, God’s providence always is, marvelous and surprising. Whenever things are given up as hopeless by human beings, then he personally gives evidence of his invincible power in every circumstance,” Homilies on Genesis 32.22.533.

“Nothing happened.”

But let’s go into the reasoning behind it. Aside from the tradition of the Church speaking authoritatively on it, there is a textual reason as well. First, the passage never states that Pharaoh took her, but only that she entered his house. Second, the phrase “Behold, your wife” is restorative, and has the meaning of “Behold, I restore to you that which I took from you.” This would not make sense if he had defiled Sarai’ai, since returning his wife would not have redressed the imbalance. Third, waiting until after Sarai’ai was defiled would have made the plagues pointless. Fourth, the timing of the plagues would be very difficult to align with a micro event such as the sexual act. After all, it has to be immediate enough that the pharaoh can mentally link it with what he is doing as the cause, and that’s a stretch to believe. The plagues themselves were a drawn out event, and so it makes sense for him to link them with a more drawn out event like having a new arrival in his home, rather than taking her into bed.

After all, when would the grand moment be? When he first approached her? Touched her? When exactly? And he would have to assess the damage done to the entire kingdom before determining that it was some form of divine judgment. Otherwise, if we are to believe it was directly tied to the sexual act, and it refers to some sort of plague immediately on pharaoh himself, why would his first thought be of Divine judgment rather than some form of sickness passed on directly by Sarai’ai? And if he did experience a personal plague from touching her sexually, why would he automatically figure out that Sarai’ai was not to be his wife? Near causes are sought before far causes. If I first take a woman as my bride, and then go to lie with her and receive a plague, I will question whether I should lie with her before I question whether I even should have taken her as my bride. The timing rather, suggests that he took a woman to be his wife, received the plagues to his kingdom, and then realized that it was the act of taking the woman into his home to be his wife that was wrong. He then gave her back to Abram.

Fifth and lastly, in the verse “And the Lord afflicted Pharaoh with great plagues,” the Hebrew “Waw” meaning “and” is antithetic, implying a contrast or reversal rather than a continuation of the previous action. Whether the “and” is antithetic in Hebrew relies on context, which has been supplied with the structure of the larger passage. In this case, the interpretation of the passage would go “It is true that the woman was taken into Pharaoh’s house, but the Lord afflicted Pharaoh, preventing any further harm and delivering Sarai from jeopardy.” 9)“In the word wayenagga’, which comes after the statement, and the woman was taken into Pharaoh’s house, the Waw is antithetic: it is true that the woman was taken into Pharaoh’s house, but the Lord afflicted the king in time, and thereby He delivered her from jeopardy,” Cassuto, Book of Genesis, 357.

By the end of it, we see the irony of an Egyptian ruler and Abram’s only wife being far more virtuous than Abram himself. The pharaoh kicking him out reminded me of when my bouncer buddy at the strip club was like “Dude you need to leave and go back to Church. This job is getting to you.” I felt stupid because he was right. The dude that knocked out gang members for fun and then snorted blow off a car hood in the parking lot was right.

So how exactly did Abram go wrong? At first glance there seems to be nothing inherently illogical or distrusting about experiencing a vicious famine and taking appropriate steps to take care of his family. How is this necessarily a lack of trust?

The passage earlier by Saint Paul gives the key. In his own stage of the Purgative Way, Abram is in a state of spiritual childhood, and when we are children we do not see clearly. When we don’t see God as he is, our charitable trust in him turns into more of a pragmatic form of trust. After all, what had God really done aside from giving him a verbal pact? Without a down payment of some form, it’s perfectly natural to assume that you are mostly on your own, or at least make preparations in case the other party should fall through. But the key word is, perfectly “natural.” With the spiritual eyes of adulthood, and trust built on a foundation of grace and charity, Abram would have seen who God truly is. God is a father that cares for his children. There is a fascinating interplay here, because often in Christianity we think of it as a good thing to come to God as a child, and yet this has to be balanced with Saint Paul’s words of seeing with the eyes of adult love.

It is so much easier to love like a child when you are a child, and yet there is a lack of depth in a child’s love. After all, a child doesn’t know how much love can hurt. A child doesn’t understand your flaws. An adult sees with the eyes of maturity, and yet knowledge of the good also means knowledge of the bad, and how much the costs can cut. That very maturity can make it harder to brave the risks. God wants both. We are supposed to love God with a clear eyed assessment of him. We should know the costs, and know who he is, and then take that childlike leap of trust anyway. That’s far harder. It is so much harder, and yet so much more rewarding. Love like a child, with the eyes of a man.

Luke 18:31-43:

31 And taking the twelve, he said to them, “Behold, we are going up to Jerusalem, and everything that is written of the Son of man by the prophets will be accomplished. 32 For he will be delivered to the Gentiles, and will be mocked and shamefully treated and spit upon; 33 they will scourge him and kill him, and on the third day he will rise.” 34 But they understood none of these things; this saying was hid from them, and they did not grasp what was said.

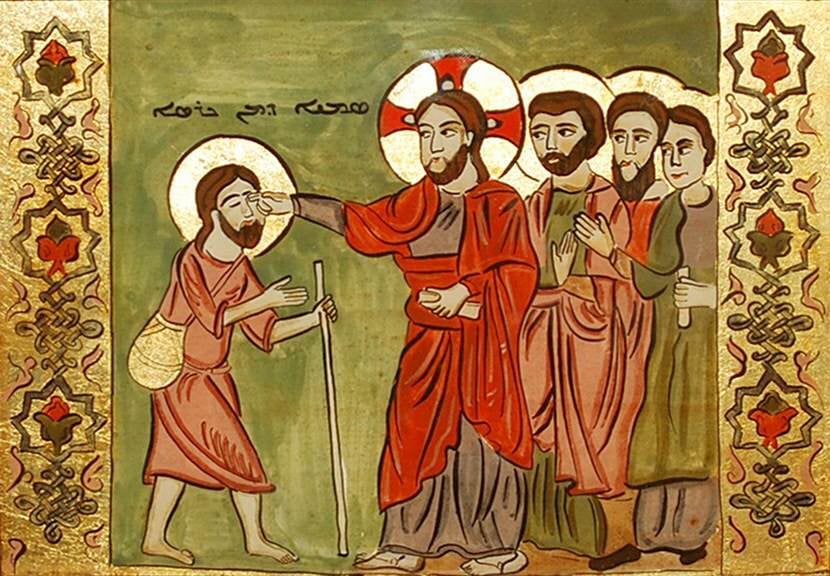

35 As he drew near to Jericho, a blind man was sitting by the roadside begging; 36 and hearing a multitude going by, he inquired what this meant. 37 They told him, “Jesus of Nazareth is passing by.” 38 And he cried, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” 39 And those who were in front rebuked him, telling him to be silent; but he cried out all the more, “Son of David, have mercy on me!” 40 And Jesus stopped, and commanded him to be brought to him; and when he came near, he asked him, 41 “What do you want me to do for you?” He said, “Lord, let me receive my sight.” 42 And Jesus said to him, “Receive your sight; your faith has made you well.” 43 And immediately he received his sight and followed him, glorifying God; and all the people, when they saw it, gave praise to God.

This final passage brings all of the readings together. Jesus explains to his disciples what love looks like, and how he will make right what the patriarchs and Israel itself did so wrong: He will choose to suffer and persevere. And his disciples, understandably and with the spiritual eyes of children, did not see nor understand what he was saying.

Back in the earlier passage in Genesis, the promise to Abram of a “great name” was that of kingship language in ancient times. Kings had “great names,” and this culminated later in the Davidic kingdom, where David himself is made a promise by God, in which a son of his line would be the messiah. 10)John Bergsma, Bible Basics for Catholics: A New Picture of Salvation History (Notre Dame: Ave Maria Press, 2012), 51. The gospel of Luke as a whole was focused on showing how Jesus was the promised son of David, and so ultimately the fulfillment of Abram’s promise as well. The logic then, is Abram’s promise > Davidic line > Jesus as fulfillment of both. Abram and David are both foundational but imperfect types to the perfect antitype of Jesus.

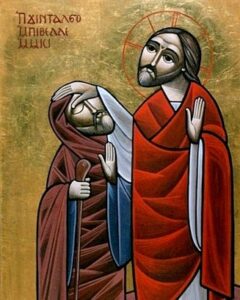

Nobody told the blind man that Jesus was the messiah, who was to come from the line of David. The crowd merely told him it was Jesus of Nazareth. And so a blind man approaches God, but they both view each other with the eyes of spiritual adulthood; the eyes of love. The man sees Jesus as he is: the messiah, and Jesus sees the blind man as he truly is: a man that can see.

Jesus asks him what he wants, and the blind man gives an answer that instantly brings to mind Saint Thomas Aquinas. Near the end of his life, Saint Thomas was asked by God what he desired and he responded “Domine, Non Nisi Te.” Lord, nothing but you. The blind man said the same thing in different words. “Lord, let me receive my sight.” But why did he want that sight? The next couple verses make that clear: to love him. He wanted to see so that he could follow and praise him; his spiritual eyes of love let him receive his physical eyes to love him even more.

Liturgical Meaning

We are to love as children, but see as adults. This Lent, we enter the desert but we must struggle against “going down into Egypt.” In the communion psalm for today, Psalm 78, David recounts the story of Israel in the desert, who unfortunately yearned for the “fleshpots of Egypt.”11)Exodus 16:3. God gives them supernatural manna, but strikes many of them dead even as the food is still in their mouths.12)Psalm 78:29-31: And they ate and were well filled,

for he gave them what they craved.

30 But before they had sated their craving,

while the food was still in their mouths,

31 the anger of God rose against them

and he slew the strongest of them,

and laid low the picked men of Israel. They received his gifts, but they received them without charity. Love of God was nowhere to be found, and they sought to procure their needs only for themselves.

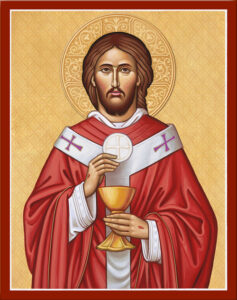

Likewise, we run the same risk of sinning unto death. If we go to Mass to receive the Eucharist but are not in a state of grace, if we take Christ without love, we profane the body and the blood of the Lord even as it is in our mouths.13)1 Corinthians 11:27-30: 27 Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord. 28 Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. 29 For any one who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment upon himself. 30 That is why many of you are weak and ill, and some have died. Instead, we should approach Christ as the blind man, with the adult eyes of love. The sacrament obscures the truth only for those that have the eyes of a child. For those that have the eyes to see, the eyes of charity, we see clearly who he is.

References

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar