Tombs, Wombs, and Unleavened Bread: Reflections on Easter Sunday

by Borderland Nathan

Mark 16:1-7:

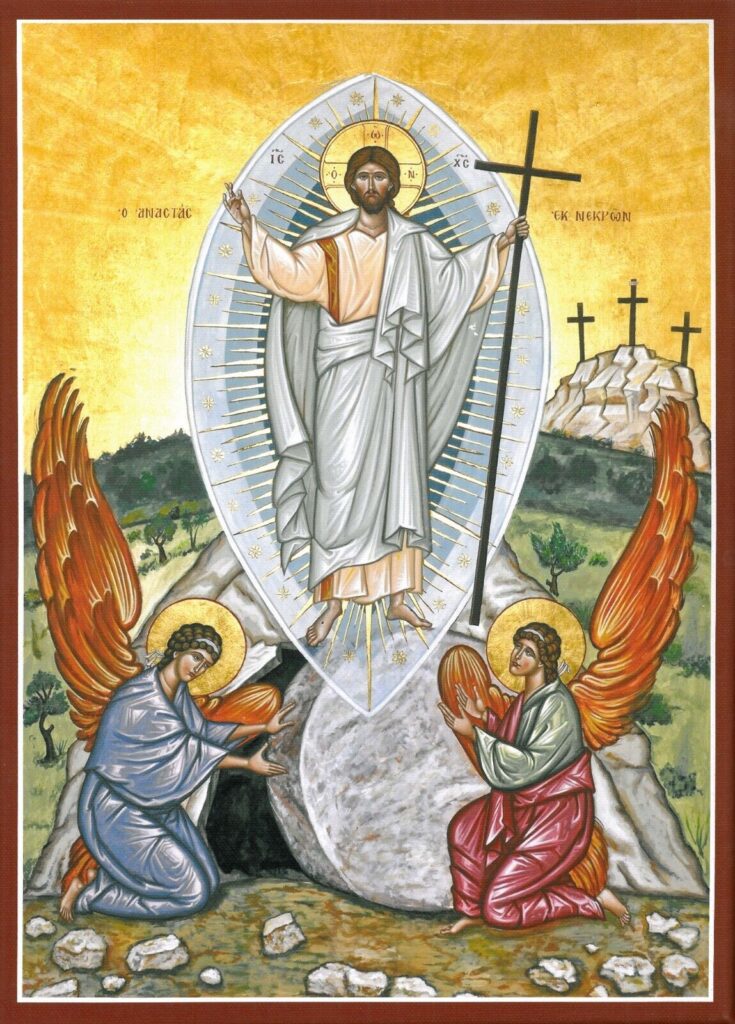

And when the sabbath was past, Mary Mag′dalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salo′me, bought spices, so that they might go and anoint him. 2 And very early on the first day of the week they went to the tomb when the sun had risen. 3 And they were saying to one another, “Who will roll away the stone for us from the door of the tomb?” 4 And looking up, they saw that the stone was rolled back; for it was very large. 5 And entering the tomb, they saw a young man sitting on the right side, dressed in a white robe; and they were amazed. 6 And he said to them, “Do not be amazed; you seek Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has risen, he is not here; see the place where they laid him. 7 But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going before you to Galilee; there you will see him, as he told you.” 8 And they went out and fled from the tomb; for trembling and astonishment had come upon them; and they said nothing to any one, for they were afraid.

Scripture enjoys using dual-sided symbols. Water is a symbol of life in some contexts such as the Creation account, and death in others, such as the flood of Noah. Likewise, baptism is a dual-side symbol that makes use of this water. It is tied mysteriously to being “born again” into new life, and yet is also tied into the death of Christ.

When Jesus and the apostles were speaking of baptism to Nicodemus, he made a connection between Jesus’s words about being “born again” and literally crawling back into the womb. Perhaps this sounded a bit thick to his listeners, but he is right in one sense: The Church fathers saw the tomb of Christ, and therefore baptism, as the womb of the Church and all Christians. Ephraem the Syrian even referred to the priest administering baptism as a midwife.

Saint Ephraem the Syrian, AD 306 – AD 373

“For by the oil of departure are anointed for absolution bodies full of stains, and they are whitened, without being beaten. They descended in debts as filthy ones and ascended pure as babes since they have baptism, another womb. Baptism’s giving birth rejuvenates the old just as the river rejuvenated Na’man. O to the womb that gives birth to royal sons every day without birthpangs! Priesthood is a servant to this womb in giving birth.”1)Ephrem the Syrian, Hymns on Virginity 7.7–8, trans. Kathleen E. McVey, in Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns (New York: Paulist Press, 1989), 294.

This shouldn’t be difficult to see why. If a womb can signify new life by being connected with baptismal waters, and a tomb can be connected with new life through baptismal waters, then through the transitive property we can see how both wombs and tombs can be equated to each other. And indeed, we see this in anthropology all over the world.2)Nurit Stadler and Shlomit Flint, “The Complexity of Architectural and Anthropological Dynamics in Womb-Tomb Structures: An Interdisciplinary Investigation,” PLoS ONE 20, no. 3 (March 2025): e0317058, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0317058.

Tombs in other societies have often not just been seen as wombs, but were carved and hacked out of stone in a way to force people entering it to feel as though they were entering one. They had to lower, much as the disciples did when entering the tomb of Jesus, sometimes even crawling, to enter increasingly narrow space that almost seemed to mimic the anatomy of a uterus.

John 20:4-5:

“They both ran, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first; and stooping to look in..”

This hearkens back to a time of primordial sacred cave architecture, when caves were most likely the first sites of our religious activities. There are many such “womb tombs” in Christianity, with specific examples including Elizabeth’s grave at the Monastery of St. John in the Wilderness, southwest of Jerusalem; the Tomb of Lazarus in the West Bank town of al-Eizariya; and the cave of the midwife Salome in Beit Guvrin.3)Nurit Stadler and Nimrod Luz, “The Veneration of Womb Tombs: Body-Based Rituals and Politics at Mary’s Tomb and Maqam Abu al-Hijja (Israel/Palestine),” Journal of Anthropological Research 70, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 184-185.

John 3:4-5:

4 Nicode′mus said to him, “How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter a second time into his mother’s womb and be born?” 5 Jesus answered, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God.

Nicodemus was correct in his imagery of the womb but incorrect in the source of the new birth. The early Christians saw the death of Christ as being present to us through baptism in the womb of the Church; our reality was spiritual rather than natural. Much as in Revelation 12, we see the Virgin Mary as the symbol of the Church. As she gave birth to the Messiah, she brought forth other spiritual children in Christ.

Likewise, her womb is the womb of the Church, and we can see this in the archaeology and iconography of our tradition. The sacred spaces where the rite of baptism was administered were themselves constructed to allude to the grave and the maternal womb.4)Robin M. Jensen, Baptismal Imagery in Early Christianity: Ritual, Visual, and Theological Dimensions (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012), 138.

![]()

I remember when there was a time that I had thought it was strange that the early Christians thought that Mary remained ever-virgin even after the birth of Jesus. The explanation given to me was that he passed through Mary as light through a windowpane. This seemed to me to be a pious but sappy belief that had more to do with strange ideas about holiness and sex than it did any kind of consistent theology. I was a fool.

If we take the tomb as womb imagery, we should note something. Matthew 28:1-2 makes clear that an angel was the one that rolled the stone away for the benefit of the women, not the risen Lord. The resurrected Christ had already passed through the stone of the tomb, and the locked door of John 20:19, in the same way that he passed through the womb of Mary. This is nothing so crass as a “Scriptural proof” for the physical integrity of Mary’s virginity. But it goes to show that the Catholic tradition has a consistent logic, and you eventually will find answers that make a beautiful sense out of the doctrines that we believe.

Saint Proclus of Constantinople, AD 390 – AD 446

“But if she remained a virgin even after birth, then indeed he was wondrously born who also entered unhindered ‘when the doors were sealed,’ whose union of natures was proclaimed by Thomas who said, ‘My Lord and my God!'”5)Nicholas Constas, Proclus of Constantinople and the Cult of the Virgin in Late Antiquity: Homilies 1–5, Texts and Translations, Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 66 (Leiden: Brill, 2003), Homily 1, 139.

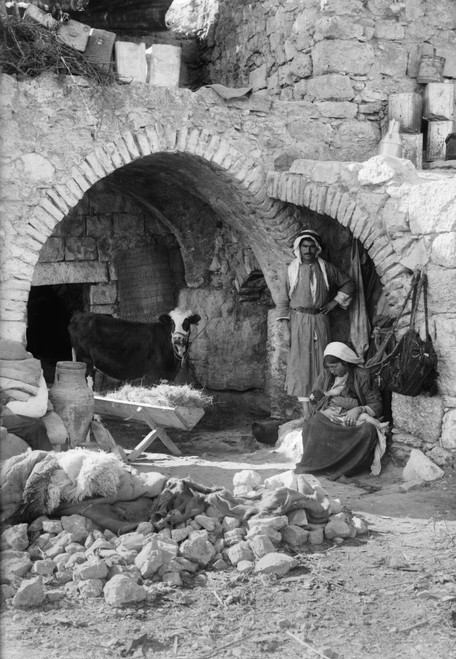

There is a final connection of womb and caves that forms an inclusio for the life of Christ, bookending the same imagery at the beginning and the end. The common tradition is that Jesus was born in a cave. Seemingly to the contrary, there is Scriptural evidence aligning with archaeology that it took place in a house, where animals were frequently brought inside during the colder times of year, both for their benefit as well as the warmth of the people inside. The further archaeological solution is that in Bethlehem, there are many houses that were built with an adjoining cave or cave basement simultaneously used as a stable for the animals. Again, the animals and people shared the same space as a form of utility and overflow area, most likely for warmth, and these structures have been found all over Judea, Samaria and Galilee, and indeed some still live in such cave homes.6)Kenneth E. Bailey, Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes: Cultural Studies in the Gospels (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2009), 29-36. The traditional site was known and turned into a holy place of pilgrimage very early, and is now the Church of the Nativity.

We have then, Jesus being born from the womb of Mary in a cave, and dying in a tomb carved out of a cave. Then he rose. For us, the womb of Mary is the womb of the Church, and baptism into the womb of the Church is baptism into the cave tomb of Christ. The early catechumens spoken of by Saint Cyril of Jerusalem would enter a tomb-like sacred space to be baptized; a cave of birth and death. And afterward, they and we, hope to rise as he did.

Saint Cyril of Jerusalem AD 315 – AD 386

“After these things, you were led to the holy pool of Divine Baptism, as Christ was carried from the Cross to the Sepulchre which is before our eyes. And each of you was asked, whether he believed in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, and you made that saving confession, and descended three times into the water, and ascended again; here also hinting by a symbol at the three days burial of Christ. For as our Saviour passed three days and three nights in the heart of the earth, so you also in your first ascent out of the water, represented the first day of Christ in the earth, and by your descent, the night; for as he who is in the night, no longer sees, but he who is in the day, remains in the light, so in the descent, as in the night, you saw nothing, but in ascending again you were as in the day. And at the self-same moment you were both dying and being born; and that Water of salvation was at once your grave and your mother. And what Solomon spoke of others will suit you also; for he said, in that case, There is a time to bear and a time to die; but to you, in the reverse order, there was a time to die and a time to be born; and one and the same time effected both of these, and your birth went hand in hand with your death.”7)Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lecture 20 (On the Mysteries. II.), trans. Edwin Hamilton Gifford, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol. 7, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1894), rev. and ed. Kevin Knight, New Advent, accessed April 27, 2025, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/310120.htm.

Now I turn to Saint Paul and we will speak of the Resurrection and its symbols.

1 Corinthians 5:7-8:

7 Cleanse out the old leaven that you may be a new lump, as you really are unleavened. For Christ, our paschal lamb, has been sacrificed. 8 Let us, therefore, celebrate the festival, not with the old leaven, the leaven of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth.

When we resurrect with Christ, we become as a new man. This new man acts in the light of grace, and this means with an upright life. Bread has always been a symbol of resurrection, and so it can rightly symbolize the moral life in Christ.

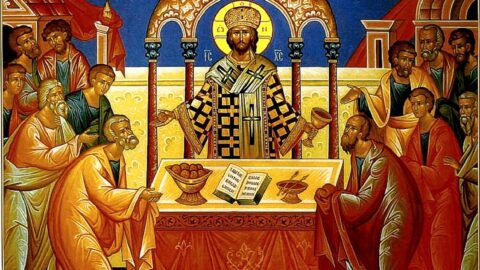

There is a disagreement between the West and the East on the matter of what type of bread best symbolizes Christ and his resurrection. In this case I refer to the Eastern Orthodox churches, as opposed to the Eastern Rite Catholics. The reason is not least that we have different ideas about which type of bread was used in the Last Supper itself to institute the Eucharist. The West uses unleavened bread, and the East uses leavened bread. Unleavened bread is flat and less fluffy than leavened bread, since leaven is the ingredient that causes the bread to rise.

I must confess that like most such disagreements, I yawn and get a bit bored. I simply don’t think they matter, because there is rich symbolism in both, and because the Council of Florence stated that both types of bread can be used as a valid Eucharist.

The East typically points to the Greek word ἄρτος, which they say refers to leavened bread, rather than ἄζυμος, which refers to unleavened, in John 13:18 and 13:26 during the Last Supper. In these passages, the bread is also dipped into something, presumably to sop up some type of sauce, and so they say it is evidence that is a soft type of bread for sopping.

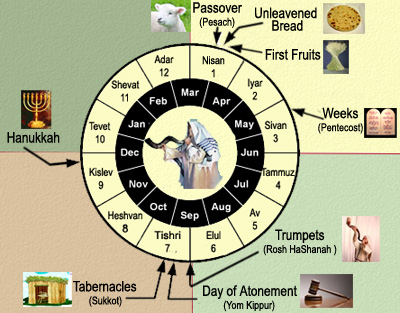

Jews followed a very old liturgical calendar, with its own months and festivals. During the “month” known as Nisan, there were two major festivals, the Passover on 14 Nisan, and then immediately after was the Feast of Unleavened Bread which lasted for seven days from 15 Nisan to 21 Nisan. They were technically two separate feasts, but the Gospels often refer to them as one eight day unit, interchangeably as “Passover” in some areas such as Matthew 26:17, and “Feast of Unleavened Bread” in others such as Luke 22:1. Mark 14:1 mentions both separately. There is a likely reason for including them in one block which I will cover later.

During these feasts, there was to be no leaven anywhere in the homes. Any bread during this time, whether Passover or the Feast of Unleavened Bread, would have to be unleavened by necessity. This is key for the argument in the East regarding the Gospel of John. The Gospel of John does not place the Last Supper explicitly at the Passover as the other three Synoptic Gospels do; in fact John 13:1 places it before the Passover, and so because of this, ἄρτος does not have to refer to unleavened bread by the context, and so it must default to its primary meaning of delicious fluffy leavened bread.

For a theological argument, the East views the unleavened bread as a simple of the Old Covenant which cannot give life, and symbolizing haste and impermanence.

Exodus 12:39:

And they baked unleavened cakes of the dough which they had brought out of Egypt, for it was not leavened, because they were thrust out of Egypt and could not tarry, neither had they prepared for themselves any provisions.

In contrast, the New Covenant bread of Christ is leavened as a symbol of the eternal covenant that gives life. Leaven raises the bread just as Christ was raised from the dead. A major strength of their position is that Jesus himself used leaven in a positive sense in the Gospel of Matthew.

Matthew 13:33:

He told them another parable. “The kingdom of heaven is like leaven which a woman took and hid in three measures of meal, till it was all leavened.”

I understand and appreciate the imagery that the East uses for their Eucharistic teaching. I particularly appreciate that they are concerned with contrasting the blessings of the New Covenant with the Old, which cannot save. But like any particular truth that is taken too far in the universal sense, I think their condemnation of the West on the issue has some serious problems.

Problem 1: It makes overgeneralized statements about the Greek

For one, the Greek word ἄρτος is a more general word that can mean either leavened or unleavened bread. That is, in fact, fatal to the entire argument, since every time we see the word ἄρτος it can in fact mean any type of bread, and all it takes is one example to the contrary to invalidate the argument. It is true that it often means unleavened bread, but in many cases it is used for different types of bread, and the more specific meaning is determined by context.

In Matthew 12:3-4 Jesus refers to the Bread of the Presence, which I have spoken about in a previous article. The word that Matthew uses for the word bread is ἄρτος, and yet we have a problem: The Bread of the Presence is unleavened. We know this because of the Jewish writer Josephus, as well as the Mishna and later Jewish writers.8)Michael P. Germano, “On the Last Supper Menu: Was It Leavened or Unleavened Bread?” Biblical Archaeology 7, no. 2 (April–June 2004): 4. Leviticus 24:5 appears to corroborate these writers by only describing the use of flour and oil, which is the simplest form of unleavened bread that you can make. Further, in the Greek Septuagint, the Old Testament as translated by Greek speaking Jews, Exodus 25:30, Leviticus 24:5-6, and I Samuel 21:3-6, all describe the unleavened Bread of the Presence with the word ἄρτος.

The Septuagint also employs ἄρτος for the unleavened bread in Leviticus 7:2 (our Leviticus 7:12), as well as the leftover unleavened bread at Leviticus 8:32. So we have more specific examples where ἄρτος without a modifier can consist of unleavened bread alone.

Finally, when Jesus appeared to the apostles after his resurrection in Luke 24:13-35, it was still during the Feast of Unleavened Bread. Again, during this time frame, no leaven could be found in Israelite homes, on pain of expulsion from the community. When Jesus broke the bread in their home, and they recognized him in the breaking of the bread, the Gospel of Luke was drawing a direct connection to the Last Supper.

Luke 24:30-31:

30 When he was at table with them, he took the bread and blessed, and broke it, and gave it to them. 31 And their eyes were opened and they recognized him; and he vanished out of their sight.

And so even if the bread of the Last Supper was leavened (it was not), Jesus chose to show himself in the breaking of the bread with unleavened as well, and again, the word used for this unleavened bread was ἄρτος. At a bare minimum, we have precedent by our Lord for using both types of bread for the Eucharist, even if every single example of bread during the Last Supper itself was leavened.

There are many such examples, more than I am interested in covering here. Suffice it to say that in the spirit of charity, when there are many examples that go directly against your main point, at the very least you should exercise caution when interpreting every occasion of the word ἄρτος as “leavened bread.” This is especially so if it forces your hand in how you interpret the Gospel of John, which brings me to my next problem with the view of the East.

Problem 2: It pits the Gospel of John vs the Synoptic Gospels

I am not very charitable to any viewpoint that speaks of contradictions between Holy Scripture. The earliest tradition of the fathers was to reconcile any perceived contradictions between the different accounts, and I think it is strange that the East would do the opposite given how strong their focus is on maintaining the traditions as handed down. John complements the other three Gospels rather than contradicts, and basing a Eucharistic theology on one Gospel at the expense of the others is faulty.9)Brant Pitre, Jesus and the Last Supper (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2015), 252.

The basic idea is that in the Gospel of John, Jesus says that they had the Last Supper “before the feast of Passover.”

John 13:1:

Now before the feast of the Passover, when Jesus knew that his hour had come to depart out of this world to the Father, having loved his own who were in the world, he loved them to the end.

The argument runs thusly. If we remember that Passover was on 14 Nissan, the assumption is that the Last Supper in John took place on 13 Nisan, the day before. Since the Jews only had to get rid of leaven on 14 Nisan, any bread used before that point could have leaven, and so any reference to bread with the word ἄρτος should be taken as fluffy delicious leavened bread.

My first response to this position is that the passage in John does not say that the Last Supper takes place a full 24 hours before Passover, but rather that it happens “before,” with the amount of time unspecified. When counting days in the Jewish calendar, it is quite similar to our current Catholic calendar. We can fulfill our Sunday obligation by going to the evening Mass on Saturday the day prior. Likewise, for the Jews the new day started on the evening of the night before, with the day bleeding into the next. We see this in Leviticus.

Leviticus 23:32:

It shall be to you a sabbath of solemn rest, and you shall afflict yourselves; on the ninth day of the month beginning at evening, from evening to evening shall you keep your sabbath.

There has been recent scholarship done on the Last Supper as a Passover meal, and this scholarship points out that the phrase in John 13:1 is referring to before the Passover lamb was eaten, not when the Passover lamb was slaughtered.

In Jewish tradition, the Passover Lamb was slaughtered on 14 Nisan, but the Passover Lamb was eaten on 15 Nisan, hence the “Feast of Passover.” This means, keeping in mind the “bleeding over” concept I spoke of above, that 14 Nisan would begin on Wednesday night (after sundown) and last up to Thursday sundown, with Thursday night being counted as 15 Nisan when the lamb would be eaten. John being “before the Feast of the Passover” on 15 Nisan on Thursday night merely places the account of John on Thursday afternoon on 14 Nisan. This is the same afternoon as the other Gospels. That means any bread during this period would be unleavened.10)Ibid., 340.

This can be seen is Numbers 28:16-17, as well as 2nd Temple Jewish literature like Jubilees 49:1-2, or later in the Mishnah. The word feast never refers to 14 Nisan, and only to the 15 Nisan, and the Mishnah refers to 14 Nisan as the eve of Passover. This would be obvious when considering that the day when the lambs were sacrificed, 14 Nisan, was a day of fasting, and so could not be a day of feasting. 11)Ibid, 342.

Remember that I said both festivals were often treated as a single block by the Gospel writers and early Jews. This is likely because the Passover and the feast where the lamb was eaten were on two separate days, and the Feast of the Passover lamb was on the first day of Unleavened Bread, and so it all ran together as a united concept.

Further, the account in John has many aspects that speak of him portraying a Passover meal, and so there simply isn’t a reason to go against all those parallels and deny the Last Supper was a Passover meal. The parallels aren’t necessary to delve into here save one, where during the Passover meal, unleavened bread was frequently dipped into a bowl of bitter herbs. And this brings us to the dipping argument sometimes pointed to by the East in the Gospel of John.

Problem 3: It assumes too much about a vague statement about bread

Unleavened bread can come in up to three forms in Scripture: a hardened cracker that must be broken, a type of pancake, and soft flat bread. The soft flat form of unleavened bread is soft enough so as to be torn. Contrariwise, leavened bread can be quite stale and hard, and have to be broken. For example, while at sea Saint Paul took leavened ἄρτος made at least 14 days earlier and “broke it and began to eat” in Acts 27:35. We simply can’t prove, then, based on such a vague argument, that broken bread = unleavened and dipped bread = soft.

Unleavened bread that can be broken

Softer unleavened bread type that can be torn.

This also makes the mistake of assuming that unleavened bread cannot be dipped. The assumption is that it is dipped into some kind of sauce to sop it up, and yet it says nothing of the sort. It merely says it is dipped, and indeed in a Passover context unleavened bread is dipped into bitter herbs, as mentioned above.

Problem 4: It attempts to prove too much with the concept of leaven

I appreciate that they use the idea of leaven as a symbol of our Lord’s resurrection, and I also appreciate that the Lord himself used leaven in a parable. And yet, the dominant concept of leaven in all of Scripture refers to sinfulness and other negative connotations. It is not just dominant, but overwhelming.

Does this mean Jesus was wrong? No. But does this mean we pit Jesus against Saint Paul and choose one over the other? No. It means that we reassess how we view leaven as a symbol. Leaven, rather than forming a hard symbol for either the good or the bad, is rather a neutral symbol that stands for exponential growth. This can refer to something good or bad depending on the context.

Saying that leaven is a symbol of our Lord’s resurrection is excellent and true. Saying that it is the best symbol for our Lord’s resurrection takes the symbol too far. I will say, that I am sensitive to the Eastern concerns of leaven being a symbol of life under the Old Law. But this brings us to my next point of contention.

Problem 5: Jesus still perfectly fulfilled the Old Law

Jesus came not to abolish the law, but to fulfill it; every “jot and tittle,” as Matthew 5:17-18 makes clear. If we rush to draw a hard break between Old and New covenants, we miss out on the rich theology of how Jesus fulfills and transcends all of the major Jewish liturgical feasts. And yet to transcend, he must first fulfill. A major cornerstone of Catholic theology is showing how for the Old Covenant to truly be dead, Jesus walked through the entire law that Israel had accumulated in its sin and then was its culmination. He took former dead signs and made them sacramental to give new life. The Old Passover, the Old Bread of the Presence, the Old First Fruits, the Old Tabernacle, the Old Sabbath, the Old purification rites involving water; Jesus and his family kept all such prescriptions and yet they all found their fulfillment in him. The dominant themes of spiritual exile, ingathering, and Passover are still present in our beliefs, with their connected symbolism.

Making a blanket statement about unleavened bread being a sign of the Old Covenant, therefore we must use leavened bread; destroys a huge chunk of theology. It makes it unclear how early Jews would have seen him as keeping God’s promises or even how they would have seen him as fitting a Messianic context, and it effectively cuts off the Old from the New. In contrast, Saint Paul goes to great lengths in his epistles to show how there is one Abrahamic covenant that grows perpetually larger, even with its unfortunate additions through sin. We must understand that we no longer need the Old Covenant ceremonies, but this does not mean completely throwing away all its symbolism for our new realities in the Body of Christ.

Liturgical meaning:

Part of the beauty of Scripture is that we see how all things point forward to Christ; the Old to the New. There is a complexity to what we see. Saint Paul talks about the law being good and not good. Symbols likewise can be helpful or not helpful, or even have a dual nature as I discussed regarding tombs and wombs. Leavened bread can represent resurrection. And yet, Saint Paul uses the opposite analogy in today’s readings and compares leaven to sin, and our new selves in Christ as being unleavened. Considering that elsewhere Paul says our new selves are linked with his resurrection, again through the transitive property we see that Saint Paul views Jesus’s resurrection with unleavened, rather than leavened bread. The East can use the leaven analogy with Saint Paul, but they cannot use their leaven analogy against him. At the very least, let there be room within the Church for both the West and the East.

Romans 6:5-12:

5 For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we shall certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. 6 We know that our old self was crucified with him so that the sinful body might be destroyed, and we might no longer be enslaved to sin. 7 For he who has died is freed from sin. 8 But if we have died with Christ, we believe that we shall also live with him. 9 For we know that Christ being raised from the dead will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him. 10 The death he died he died to sin, once for all, but the life he lives he lives to God. 11 So you also must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus. 12 Let not sin therefore reign in your mortal bodies, to make you obey their passions.

References

Rob Brotzman

Rob Brotzman  Nathan Wagar

Nathan Wagar